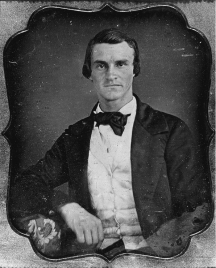

James R. McClintock, the inventor of the H.L. Hunley, shortly before journeying to Boston in February 1879–apparently to meet his end there. Image: Naval Historical Center.

At a quarter to nine on the evening of February 17, 1864, Officer of the Deck John Crosby glanced over the side of the Federal sloop-of-war Housatonic and across the glassy waters of a calm Atlantic. His ship was on active duty, blockading the rebel port of Charleston from an anchorage five miles off the coast, and there was always the risk of a surprise attack by some Confederate small craft. But what Crosby saw that night, by a wintry moon that barely illuminated the dark ocean, was a sight so strange that he was not at first quite certain what it was. “Something on the water,” he recalled it to a court of enquiry a week later, “which at first looked to me like a porpoise, coming to the surface to blow.”

Crosby told the Housatonic‘s quartermaster of the object, but it had already disappeared–and when, a moment later, he saw it again, it was too close to the sloop for there to be time to slip the anchor. The Housatonic‘s crew scrambled to their action stations just in time to witness a substantial explosion on their starboard side. Fatally holed, their ship sank in a few minutes, taking five members of her crew with her.

It was not clear until some time later that the Housatonic had been the first victim of a new weapon of war. The ship–all 1,240 tons of her–had been sunk by the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley: 40 feet of hammered iron, hand-cranked by a suicidally brave crew of eight men, and armed with a 90-pound gunpowder charge mounted on a spar that jutted, as things turned out, not nearly far enough from her knife-slim bow.

The story of the Housatonic and the Hunley, and of the Hunley‘s own sinking soon after her brief moment of glory, of her rediscovery in 1995 and her eventual salvage in 2000, has been told many times. We know a good deal now about how the submarine came to be built – of her funding by a patriotic Southerner named Horace Hunley, the construction of two prototypes, and how the Hunley herself was riveted together at Mobile – not to mention the design defects and the human errors that drowned two earlier Hunley crews, 13 men in all. We also know a little of the men who did the actual work: James McClintock and Baxter Watson, two talented mechanics who were running a steam gauge business in New Orleans when the war broke out. We even have a shrewd idea of the division of labor between the two men, for Watson’s son once confided that while his father had built the Hunley, it was McClintock who designed her. Of the three men responsible for the Hunley, then, it was probably James McClintock who played the most important role–and, as thing turn out, it is McClintock who also has by far the strangest tale to tell.

The sinking of the Housatonic. Contemporary sketch by–probably–the artist William Ward. Image: Library of Congress.

The central mystery of McClintock’s life, in fact, involves his death in 1879. We know what is supposed to have happened to him in that year, for his own grandson, Henry Loughmiller, writing to the early Hunley researcher Eustace Williams sometime prior to 1958, baldly stated: “He was killed at the age of 50 in Boston Harbor when he was experimenting with his newly invented submarine mine.” Loughmiller’s account has been picked up and accepted by every one of the dozens of authors who have written about Confederate submarines in the half century since then. Yet fresh research suggests that each part of his sentence can be challenged. Those who met McClintock in 1879 thought him much closer to 60 years old than 50; the explosion that supposedly claimed his life took place outside the confines of Boston Harbor; and, strangest of all, the evidence that McClintock was actually killed by it is remarkably flimsy. Many people heard the explosion, but not a single person actually witnessed it. There was no corpse. There was no inquest. Not so much as a shred of mangled flesh was ever recovered from the water. And 16 months later, in November 1880, a man who said his name was James McClintock walked into the British consulate in Philadelphia to tell a most outlandish tale and offer his services to Queen Victoria as a secret agent.

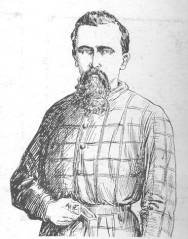

James McClintock’s invention, the submarine H.L. Hunley, on a jetty at Mobile. Only a few weeks earlier, the submarine had sunk during a trial, killing all eight members of her crew. Detail from a contemporary painting by Conrad Wise Chapman.

The events that led McClintock to Boston in the winter of 1879 had their beginnings not in a besieged Charleston but in a boyhood spent navigating the great rivers of the American interior. Census records confirm that the submarine inventor was born in Ohio, and family tradition suggests that he grew up in Cincinnati and left home at an early age to join the crew of one of the great riverboats that plied the Mississippi, acquiring sufficient experience and skill to become “the youngest steamship captain on the river” in the years before the outbreak of the Civil War. At some point, McClintock also began to show talent as an engineer and inventor. Caught in New Orleans by the war, he and his partner Baxter Watson drew up the plans for a new machine for making Minié balls, the rifled musket bullets used by both sides throughout the conflict. According to the New Orleans Bee, the two men boasted that their invention would cost only $2,000 or $3,000 to make, and “with it two men can turn out a thousand balls per hour, or with steam power it makes eight or ten thousand per hour. This one machine, worked night and day, could turn out 1,200,000 balls every week, more than enough to supply the Confederate armies in the most desperate and extended war possible.”

The Minié ball machine was never made–an indication, probably, that its real worth had been thoroughly exaggerated. But it served as a calling card, and must have helped to persuade Hunley to assemble a consortium that invested somewhere north of $30,000 in McClintock’s submarines. Reading between the lines of Civil War accounts, it seems likely that it was the desire to recover this investment, as much as patriotic fervour, that persuaded the boats’ owners to persevere in the face of repeated disaster: at least three sinkings, reported stiflings and near-stiflings, and even the death of Horace Hunley himself, who, having fatally dived to the bottom during trials at Charleston in October 1863, was recovered from his salvaged submarine three weeks later–”a spectacle,” one contemporary report related,

indescribably ghastly; the unfortunate men were contorted into all kinds of horrible attitudes, some clutching candles, evidently attempting to force open the manholes; others lying in the bottom, tightly grappled together, and the blackened faces of all presented the expression of their despair and agony.

New Albany, Indiana, in the middle of the 19th century. The township stood on the north bank of the Ohio river, which during the Civil War marked the border between Union and Confederate territory.

Of all the men known to have boarded the Hunley, indeed, only about half a dozen escaped death in her iron belly – yet McClintock himself survived the war, and one of the keys to understanding the events of 1879 is to establish why he did so. It was not, apparently, because he declined to take the risk of diving in his own submarines; he conducted most of the preliminary experiments himself. Rather, the inventor claimed, his own skill and caution kept him alive while others died in his inventions. When, in the fall of 1872, McClintock traveled to Canada in an attempt to sell his submarine designs to the Royal Navy, the officers who interviewed him proclaimed themselves “strongly impressed with the intelligence of Mr McClintock, and with his knowledge on all points, chemical and mechanical, connected with torpedoes and submarine vessels.”

The circumstances that led McClintock to Boston are only hazily known. By 1879 he was living in New Albany, on the Ohio River at the southern tip of Indiana, where – having failed in an attempt to promote a new sort of concrete sidewalk in Philadelphia – his occupation was recorded as “salesman.” This suggests that a considerable reversal of fortune had occurred to him since 1872, when he had been the moderately prosperous owner-operator of a dredge boat on Mobile Bay. He was also married and the father of three teenage daughters, and the evidence of 1872 suggests that he was keen to leverage his expertise in building secret weapons to make a fortune in the shady private armaments market. By 1877, certainly, he had established contact with two other men who shared these views–George Holgate, a Philadelphian then just setting out on what would become an infamous career as a free-lance bomb-maker, and the mysterious J.C. Wingard, who was by profession a New Orleans river pilot and who had worked with McClintock in Mobile during the war.

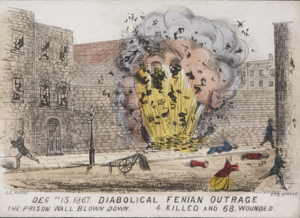

The Clerkenwell explosion, on December 13, 1867–part of an attempt to rescue several Irish republicans from a London jail–focused British attention on bomb-makers.

Both these men, it is fair to say, were extraordinary characters. Holgate, who seems to have been born in lowland Scotland, was the prolific inventor of an alarming collection of elaborate explosive devices which he hawked indiscriminately to all comers–Irish freedom fighters, Cuban patriots and Russian nihilists. Wingard was even more remarkable. When an early sideline as a prominent medium was disrupted by the Civil War, he too turned to invention, re-emerging in New Orleans in 1876 as the proprietor of a death ray that he claimed was powerful enough to annihilate enemy ships across several miles of open water.

It is worth pausing here to look in greater detail at the two chancers with whom McClintock chose to associate himself. Holgate was a would-be criminal mastermind who would, within a year or two, delight in giving interviews in which he trumpeted his lack of principles. “I no more ask a man,” he informed one newspaper reporter who had enquired about his customers, “whether he proposes to blow up a Czar or set fire to a palace… than a gunsmith asks his customers whether they are about to commit a murder.” His past was murky. He claimed to be the former proprietor of a London paint shop which had actually been a front for a bomb-making business, though there is no trace of any such activities in a British press that became obsessed with bombers when the Irish Republican Brotherhood–a precursor to the IRA–began using them in London from 1867.

By the early 1870s, in any case, Holgate was certainly living in the United States, where he pitched up in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, purchasing a gun shop and touting a highly dubious invention which, he boasted, used injections of ozone to keep fruit, vegetables and even beef fresh for weeks. He was, the local Northwestern newspaper would recall, a “blatherskite” and “blowhard… one of those wild erratic individuals who now-a-days are gaining such cheap notoriety by cheap means.” But he was also–potentially, at least–a very dangerous man. The wares that he touted, Ann Larabee records, included a good deal more than mere conventional explosives:

a cheap hand grenade, a bomb concealed in a satchel that had a fuse running through its keyhole, and a hat bomb comprised of dynamite pressed between two sheets of brass sewn into the crown with a fuse running around the rim. His “Little Exterminator” operated through a delicate watch mechanism that moved a tiny saw, releasing a chemical that smelled like cayenne pepper, killing anyone within one hundred feet.

The Tennessee preacher Jesse Babcock Ferguson witnessed Wingard’s mediumistic performances–and was convinced of their veracity.

James Wingard had enjoyed, if anything, an even more peculiar career. In common with most of the men who earned their living on the Mississippi, “Captain” Wingard was almost entirely uneducated–”a plain, simple, straightforward man,” Emma Hardinge wrote in 1870. He exhibited, nonetheless, extraordinary talents as a medium. The great spiritualism craze, which had burst on the United States late in the 1840s, quickly developed its own specialisms, and Wingard became renowned as early as 1853 as a faith healer and for the “spirit drawings” that he produced in darkened seance rooms “on paper which had previously been examined and found not to contain any marks.” His most remarkable performances, however, involved the production of automatic writing, messages that were supposedly produced by spirits that had taken control of a medium’s body, though in Wingard’s case the performance would have been acclaimed had it been performed on stage. According to Thomas Low Nichols, the revivalist preacher Jesse Babcock Ferguson swore that he had seen Wingard “write with both hands at the same time, holding a pen in each hand, sentences in different languages, of which he was entirely ignorant. He saw him, as did many other persons of undoubted credibility, write sentences in French, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic.”

The Civil War found Wingard in New Orleans, and changed him. Just as the crisis had turned James McClintock’s interests towards bullets, it focused Wingard’s thoughts on an early sort of machine gun. This device was never built, but like the Minié ball machine it was extravagantly promoted. Wingard claimed that weapons made to his design would be capable of discharging bullets at the rate of 192 a minute “at a range as great as any gun then in use.”

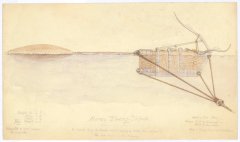

Wingard’s “Nameless Force” makes the press. An advertisement placed by the inventor in the the New Orleans Times-Picayune of May 7, 1876.

What makes all this noteworthy is that Wingard’s interest in mechanical death-dealers persisted after the war, and early in 1876 he reappeared in New Orleans touting a still more remarkable invention. Now calling himself “Professor” Wingard, he claimed to have invented an astonishing new weapon capable of annihilating enemy warships at a distance of anything up to five miles. The manner in which this destruction was to be effected was left vague, though Wingard went so far as to explain that his weapon utilised electricity, which in the 1870s was for many still mysterious; it seemed not at all impossible that it might be able to destroy targets–as Wingard claimed– so utterly that it would “leave no trace of them in their former shape.” But there was more to the supposed invention than this, for in the advertisements that he placed in the New Orleans press, and the interviews that he gave to journalists, Wingard spoke of a “Nameless Force” which in some mysterious way transmitted electrical power across water and focused it upon its target. The Nameless Force, he confidently promised, was destined to become “a factor controlling the destinies of a nation.”

The result of all this public relations work was a tremendous interest in Wingard’s invention that somehow survived two unsuccessful efforts to demonstrate the Nameless Force on Lake Pontchartrain. Chastened by his double failure, Wingard decided not to invite the New Orleans public to witness a third attempt on June 1, 1876, but a “committee of gentlemen” was present when, at 2.35pm, the Professor discharged the weapon from a small skiff. It was aimed at an old wooden schooner, the Augusta, which had been anchored about two miles away, off a popular amusement park on the southern shore known as the Spanish Fort.

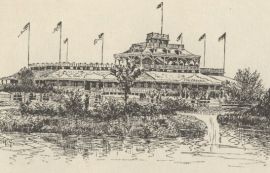

The Spanish Fort amusement park on Lake Pontchartrain was the spot chosen by “Professor” Wingard for a public demonstration of his Nameless Force.

This time, it seemed, the Nameless Force took effect, and the Augusta “suddenly blew up” about 90 seconds after Wingard’s invention was discharged. When the witnesses reached what remained of the vessel, they found her “shattered in small fragments,” and it seemed all the more impressive that Wingard “could not receive the congratulations of his friends” as he had somehow sustained bad burns to one hand in the course of the operation.

From our perspective, the most important outcome of the demonstration was not Wingard’s brief lionization in New Orleans, but a deflating coda reported by the Galveston Daily News a few days later. According to that paper, “a delegation of newsboys, who happened to be in the vicinity, with a spirit of scientific research… visited the schooner despite repeated warnings to keep away, and reported that they found a large gas pipe filled with powder, and a wire leading towards [the skiff] that was anchored some distance away.” The entire demonstration, in short, had been a fraud; the only “force” involved, the News concluded, was a quantity of gunpowder concealed beneath the Augusta’s decks, and a long wire, “tightened by means of a windlass on the skiff,” which triggered the detonation of the explosives. This discovery dented Wingard’s reputation, and he seems not to have been heard from again until he unexpectedly appeared in Boston late in 1879.

What happened to the trio of would-be death-dealers that October can be established from local newspaper reports. These show that the men appeared in Boston in the first days of the month, that they had chartered the steamboat Edith, and that on October 13 they hired a second boat, the yacht Ianthe, with a rowboat as tender, from a local firm named Hutchins & Prior. Hutchins supplied a Nantucket man, Edward Swain, as crew, and on that same afternoon Swain sailed Ianthe to a spot off Point Shirley, to the east of Boston Harbor. It is at this point that accounts become confused, but the most considered and most detailed state that Wingard had taken command of the steamer and was towing an old hulk, which was to be used as a target. Holgate had been due to join Swain in the tender, but complained of seasickness and retired into Ianthe‘s deckhouse to lie down, so McClintock took his place, carrying with him a “torpedo” – mine – packed with 35 pounds of dynamite, which (the Boston Daily Advertiser reported) he had boasted was powerful enough to “blow up any fleet in the world.”

Shortly thereafter, with the tender about a mile from the Ianthe and two miles from the Edith, there was an ear-shattering explosion. Wingard, speaking to the Advertiser, claimed that he had been “looking the other way” at the fatal moment, but turned in time to see a column of spray and debris rising high into the air. Holgate, who said he had been lying in his bunk, likewise missed the explosion, but when the Ianthe and the Edith converged on the spot there was no trace of McClintock or Swain; all they could see floating on the surface was a mass of splinters.

Neither Holgate nor Wingard seem to have been at all anxious to make comments to the press, and both men quickly left Boston – Holgate after securing McClintock’s possessions from his hotel bedroom and without reporting the incident to the police: “He had a horror of recounting the event,” the Philadelphia Times explained after interviewing the old bomb-maker two decades later, “and so he said: ‘There can’t be an inquest unless there is a body to hold it upon, and there is not even a scrap left of my unfortunate companions.'” Indeed, perhaps because neither of the victims was Bostonian, the authorities seem to have taken remarkably little interest in what had happened. I have found no trace that there was ever any real investigation, nor even much curiosity as to why a trio of civilians were experimenting with such a powerful explosive charge.

A Harvey towing torpedo – one of a new generation of weapons being developed in the 1870s. According to George Holgate’s version of events, McClintock’s fatal “torpedo” was a device of this type.

Thus far, the account found in contemporary reports contains nothing to contradict Henry Loughmiller’s belief that his grandfather died that day in Boston. Read carefully, however, the surviving accounts do contain some odd pieces of testimony that simply do not mesh with the tales that Holgate and Wingard recounted. The Daily Globe, for instance, reported that Holgate’s involvement in the tragedy had been considerably greater than he was willing to admit; the “torpedo” was electric, the Globe explained, and the explosion had occurred when Holgate somehow set the charge off remotely. Strangest of all was a note in the same paper stating that a reliable witness–a hunter out shooting at Ocean Spray–had seen McClintock’s rowboat still afloat after the explosion, “so that the men, he thinks, could not have been blown to pieces.”

Nothing came of any of this at the time. Holgate hastened to New York, and then home to Philadelphia, wiring McClintock’s family–so he said–to tell them of the awful accident. Wingard vanished. Boston’s harbor police dropped the half-hearted enquiries they had made, and nothing more was heard from any of the participants for more than a year.

A good deal did happen in the interim, however, and perhaps the most significant of these developments took place in New York, where an ambitious splinter group from an Irish secret society known as the Clan na Gael had begun to plan a large-scale terrorist campaign on the mainland of Britain–the first, in fact, that there had ever been there. Led by Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, an Irish journalist who had been elected “Head Centre” of the entire Fenian movement in the USA, it began raising funds and looking for ways to manufacture bombs and smuggle them across the Atlantic.

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa–blowhard, Irish freedom fighter, and would-be mastermind of Irish republicanism’s first major British mainland bomb campaign.

O’Donovan Rossa and his associates were nothing if not ambitious–they raised $43,000 [just over $1 million today] with the aim of spreading “terror, conflagration, and irretrievable destruction” the length and breadth of England, and even established a “Dynamite School” in Brooklyn to teach recruits how to make, conceal and use their bombs. But the loose-lipped Rossa was also enduringly indiscreet about their plans, and by the fall of 1880–a year after the explosion in Boston, but months before their terror campaign was due to begin–British diplomats in the United States were already at a state of high alert, and desperately seeking information about how exactly Rossa planned to spend his money.

It was against this background that Robert Clipperton, the British consul at Philadelphia, received an unexpected visitor in October 1880. This man introduced himself as James McClintock, explained that he had a background in submarine and mine warfare–and revealed that he had been hired by Rossa’s Skirmishing Fund to build 15 examples of a new sort of torpedo so powerful, he boasted, that a single weapon filled with 35 pounds of explosives “could sink an ironclad if exploded under her bottom, and could be carried in a great-coat pocket.”

The Philadelphia McClintock’s purpose in calling on Clipperton was to offer his services as a double agent. In exchange for payments of $200 [equivalent to $4,650 today] each month, he was willing to betray his employers, slow down the work, hand over samples of the weapons, and guarantee not to supply working models to Rossa’s terrorists. Asked why, he replied that “to speak plainly, he was after money.”

Clipperton was impressed by his visitor, and so were his masters in the British embassy at Washington. The British naval attaché, Captain William Arthur arrived post-haste in Philadelphia, where on November 5 he met with McClintock and recommended his recruitment as a spy. The weapons, Captain Arthur wrote, seemed viable, and the informant’s plans were workable–the real doubt was his honesty, not truthfulness. As a result of this report, the man calling himself McClintock was paid $1,000, and Clipperton and his assistant, George Crump, continued to meet with him well into 1881. That March, the consul was handed samples of three different sorts of bomb–one disguised as a lump of coal and intended to be slipped into the bunkers of a transatlantic steamship, to explode with catastrophic consequences when it was shoveled into a furnace while the ship was out at sea.

Alfred Nobel’s great invention, dynamite–a stablilized form of nitro-glycerine–was the weapon of choice for a new generation of bombers–including Philadelphia’s George Holgate.

Who, though, was the man whose appearance in Pennsylvania caused Clipperton’s diplomats so much concern? The first thing to say about him is that he was just as slippery and traitorous as he appeared to be. By the time the official correspondence–lodged today in Britain’s National Archives–petered out in July 1881, he had successfully extracted a four-figure sum from both Rossa’s Irish freedom fighters and Queen Victoria’s secret service fund. He had managed this, moreover, while cheating and betraying not one but both of his employers. Rossa never received his final consignment of torpedoes, but the samples that McClintock supplied to the British were not the real thing, either–“the contents of his cases,” a worried official reported from London when the test results came in, “are not dynamite, but a powder made to resemble it of a very slightly explosive quality.” In the last analysis, moreover, the Philadelphia McClintock got away with everything, slipping away before either the British or the Fenians could lay their hands on him. It seems to be the case that he was never heard from again.

There are certainly problems with the idea that the McClintocks of 1879 and 1880 were one and the same. One is that the real James McClintock never returned to his family. He was listed as dead–killed in Boston–in the mortality schedule for 1880 that was compiled in New Albany, and his grandson knew of nothing, nearly a century later, to suggest this was not the case.

For McClintock to have survived the explosion, moreover, requires him to have been something more than simply the victim of shoddy Boston newspaper reporting; Holgate was still vividly retelling the story of his atomization as late as 1896. For the Confederate submariner to have still been alive in 1880 would have meant that he had deliberately set out to fake his death–and, probably, to become a murderer as well, for the unfortunate Edward Swain was also never seen again. McClintock would surely have needed a good reason to take these drastic steps, but it is possible to speculate that he had one–by the time he got to Boston, he was definitely short of money, and a spectacular apparent death might have seemed a good way to escape his creditors, or some backer calling in a debt.

In the final analysis, however, there is no way to be certain that McClintock was desperate, and there are really only two ways to determine whether Clipperton’s informant really was the man he said he was. One is to ask whether the events of 1879 make any sense viewed as a fraud. The other is to search the British archives for scraps of information that could only have been provided by the real McClintock.

There is evidence, as we have seen, that the Boston explosion may not have taken place in the way it is supposed to have. No one saw the rowboat disintegrate, nor found any trace of bodies. But it strains credulity to suppose that McClintock rigged an explosion and then made a clean getaway without assistance from Wingard and Holgate. It would have been all but impossible to escape the scene without being observed by one of them.

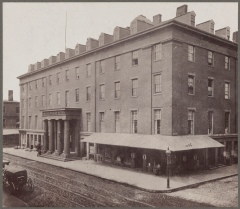

“Professor” Wingard put himself up in Boston’s sumptuous United States Hotel, pictured here in 1883. McClintock and Holgate stayed at the less ostentatious Adams House.

That the two men might have helped McClintock fake his death is not entirely implausible; neither was a paragon of decency. But it is hard to imagine what their motive might have been, unless McClintock was their boss and paying them. Holgate’s accounts, in fact, suggest this was the case–he went to great lengths to stress just how little he had really had to do with the experiments. But then Holgate must have feared implicating himself, and there is in fact another clue, long buried in the archives of the Boston Daily Advertiser, which suggests that things in fact went differently: according to the Advertiser’s files, Wingard lodged at the United States Hotel, while McClintock and Holgate put up at the Adams House.

This, it turns out, is a telling detail, for in 1879 the United States was Boston’s second-best hotel, while the Adams House was a far less imposing establishment. From this it seems logical to conclude that it was Wingard, and not Holgate and McClintock, who was in command of the experiments in Boston, and a solitary report in Chicago’s Daily Tribune seems to confirm it. In the Tribune’s version of events, Wingard’s real reason for traveling to Boston was to stage another fraudulent trial of his Nameless Force for the benefit of fresh investors, and he spent the first half of October assembling a joint stock company willing to plough $1,500 into his spurious death ray. The explosion put an end to that (the Tribune wrote), and a shaken Wingate actually confessed to his investors that the blast had taken place while two of his men were on their way to install hidden charges on the hulk selected for his demonstration.

If Wingard had nothing to do with McClintock’s disappearance, though, only two possibilities remain. One is that McClintock died, and that Holgate was an opportunist. In this scenario, the Philadelphia informant was Holgate, posing as his old partner in order to prise money from the British. A couple of details suggest that this might actually have been the case. One is that ‘McClintock’ chose to reappear in Philadelphia–which was, by 1880, Holgate’s home. The other is that the man who turned up at the British consulate explained that his device contained a very specific charge–35 pounds of explosives. Presumably not coincidentally, that was precisely the size of the device that Holgate told the Boston press had blown up James McClintock.

A pre-war Daguerrotype of James R. McClintock. Inventor, likely crook, possible spy. Born ?1829. Died ?1879.

Image: Naval Historical Center.

The alternative scenario is that Holgate and McClintock were in fact in league. In this interpretation, McClintock simply stayed on board the Ianthe and sent Swain off to die in his stead in the rowboat. Knowing that the explosive charge was designed to be detonated remotely by wire, just as it had been in New Orleans, adds some weight to this theory, for if Swain rowed off trailing cable, as he must have done, the charge could have been detonated at any point–and, just as the Boston Globe alleged, the explosion might have been triggered by Holgate. All McClintock needed to do at that point was to stay below while the Ianthe and the Edith converged upon the fatal spot. Wingard need have been none the wiser, McClintock (presumably) escaped his creditors, and Holgate gained himself a sleeping partner with useful experience of explosives and of underwater warfare.

It may be that we will never know for sure. The papers in the British archives contain no physical description of Clipperton’s informant, and all that can be suggested with much certainty is that the strange coincidence between the size of the charge used in Boston and the one offered to the British a year later means that the man who appeared in Philadelphia was not some unknown third party; it must have been either Holgate or McClintock.

If it was Holgate, though, why bother to pose as his former partner? It is true that Holgate was no expert in underwater warfare, while McClintock was. But it defies belief to suppose that McClintock’s name would have carried weight with any British diplomat in 1880. His role as the designer of the Hunley had never been disclosed. His visit to Canada was a state secret. And it would not be until well into the next century that his role in the destruction of the Housatonic would be celebrated.

Bearing all this in mind, perhaps the salient point is this: the Philadelphia McClintock was able to convince the British naval attaché, Captain Arthur, that he knew all about both mines and submarines. This would not have been an easy trick to pull, for it so happened that Arthur was himself an expert; his last posting, before coming to America was as Captain of HMS Vernon – and the Vernon was the Royal Navy’s chief research establishment for underwater warfare. So maybe, just maybe, the triple agent who tricked the British and the Irish terrorists in Philadelphia, and got away with $2,000 and his life, was precisely who he said he was: James R. McClintock, inventor of the HL Hunley, betrayer of countries, causes, friends and his own family, and the faker of his own strange death.

Sources

Primary: British National Archives: Admiralty papers. ‘Submarine warfare,’ 1872, Adm 1/6236 part 2; ‘Fenian schemes to employ torpedoes against HM ships,’ 1881, Adm 1/6551; digest for August 9, 1872 and October 19, 1872 at cut 59-8 of Adm 12/897; digest for February 8, 1873 at cut 59-8 of Adm 12/920. Foreign Office Papers. New Orleans consulate. Cridland despatch no.2 commercial of April 5, 1872 enclosing statement by James McClintock, March 30, 1872, and Cridland to Foreign Office July 17, 1872, both in FO5/1372; Fanshawe to Cridland, December 20,1872, Cridland despatch no.7 commercial of January 3, 1873, McClintock to Cridland, January 7, 1873, Cridland to Foreign Office, May 25, 1873, all in FO5/1441. Philadelphia consulate. Political correspondence for 1881 in FO5/1746 fols.100-02, 146-7; FO5/1776, fols.65-71, 80-5, 247, 249, 265, 291; FO5/1778 fols.289, 403; United States censuses 1860 and 1870; Eustace Williams, “The Confederate submarine Hunley documents,” np, Van Nuys, California, 1958, typescript in the New York Public Library. Secondary: Anon. “Some scientific hoaxes.” In Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science, and Art, June 12, 1880; Victor M. Bogle. “A view of New Albany society at mid-Nineteenth Century.” In Indiana Magazine of History 54 (1958); Boston Daily Advertiser, October 15, 16, and 20, 1879; Boston Evening Transcript, October 15, 1879; Boston Daily Globe, October 14, 15, 16 and 20, and November 17, 1879; Boston Weekly Globe, October 21, 1879; Carl Brasseaux & Keith P. Fortenot. Steamboats on Louisiana’s Bayous: A History and Directory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004; Chicago Daily Tribune, November 14, 1879; Mike Dash. British Submarine Policy 1853-1918. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of London 1990; Esther Dole. Municipal Improvements in the United States, 1840-1850. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Wisconsin 1926; Ruth Duncan. The Captain and Submarine H.L. Hunley. Memphis: privately published, 1965; Charles Dufour. The Night the War was Lost. Lincoln NE: Bison Books, 1964; Eaton Democrat (OH), June 20, 1876; Floyd County, Indiana, mortality schedule, 1880; Galveston Daily News, June 6, 1876; Emma Hardinge. Modern American Spiritualism: A Twenty Years’ Record. New York: The Author, 1870; Chester Hearn. Mobile Bay and the Mobile Campaign: the Last Great Battles of the Civil War. Jefferson [NC]: McFarland & Co., 1993; Ann Larabee. The Dynamite Fiend: The Chilling Tale of a Confederate Spy, Con Artist, and Mass Murderer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005; New Orleans Daily Democrat, March 22, 1877; New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 12+May 30+June 4, 1876; New Orleans Daily Times, October 15, 1879; Thomas Low Nichols. Supramundane Facts in the Life of Rev. Jesse Babcock. London: F. Pitman, 1865; Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, March 21, 1883; Ouachita Telegraph [LA], November 14, 1879; Philadelphia Times, September 21+February 26, 1896; Mark K. Ragan. Union and Confederate Submarine Warfare in the Civil War. Boston: Da Capo Press, 1999; Mark K. Ragan. The Hunley. Orangeburg [SC]: Sandlapper Publishing, 2006; KRM Short. The Dynamite War: Irish-American Bombers in Victorian Britain. Atlantic Highlands [NJ]: Humanities Press, 1979; Niall Whelehan. The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World, 1867-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Reblogged this on Mysterious Times.

I love the shenanigans folks could get up to in those days of loose identity.

Great story; thanks for posting it!

I know a ton of former submariners who can relate to all this

Interestingly, I’m currently sitting in my office about half a mile from where the Hunley currently sits. It’s part of a museum now where you can take tours. The history of the submarine is fascinating and a bit terrifying if you’re not a fan of enclosed spaces.

Prior to 1968 the US government encouraged inventors to work with explosives, and, of course, the military interest in weapons never ends.

Thus, the fact that the men were working with fairly large amounts of materials isn’t unusual.

This story has everything – the world’s first submarine, con-artists, a spiritual medium, irish terrorists, secret bomb-makers, spies…

[…] The curiously tangled story of James R. McClintock, inventor of the H.L. Hunley […]

You make a better case, I think, that it was the imposter who turned up in Philadelphia the year after the explosion. But the story line of someone who may have faked his own death makes for good speculation.

I missed these kinds of posts from you! Love to escape into a good mystery. 🙂

[…] It’s Weird History Wednesday, so brace yourselves for a possibly true story of murder (maybe), mayhem (arguably so), explosions (definitely), and a triple agent submarine mechanic (maybe) […]

Fascinating story!

Anyone who reads that entire thing is worthy of praise.

What, are you suggesting that it’s not entirely interesting and worthy of praise? If you don’t like this, then you have no business reading history at all, and would be better off in front of a TV, getting bored with any topic or scene that lasts more than 3 seconds because you have the attention span of…well, the typical modern American.

It’s a very interesting tale, full of James Bond like intrigue. I do recommend a full read through.

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

One of four survivors of the H. L. Hunley that sank while being tested was named Jeremiah Donivan (spelled with an “i”). Does anyone know if this is the same person named “Jeremiah O’ Donavan Rossa”, Irish Freedom Fighter and bomb maker. If so, when did the “Rossa” get added to his name? Not much is known about this person.

It’s not the same person, I’m afraid. O’Donovan Rossa was in a British prison for the duration of the Civil War, and did not emigrate to the US until 1871.

No they are not the same person, but they are related

This McClintock guy is rather creepy…

You ask why Wingate would have bothered to assume McClintock’s identity? He’s about to rip off both the Fenians and the British government…why would he want them to know his real name? When you’re a con-artist, you never give someone your name if you can help it. I suspect Wingate was a deeper file than people suspected, and was the one who got away with everything in the end; learned about subs from McClintock, killed him for money or something else, and then stole his name, just for the heck of it. Shades of “The Usual Suspects”!

Would make a great movie or TV show. Could you expand on it ?

A book on my relative will be out next year. Perhaps a movie will come from it.

Pingback: Infernal Machines in the Saturday Evening Post of 1881 - TechCodex